--The blurb--

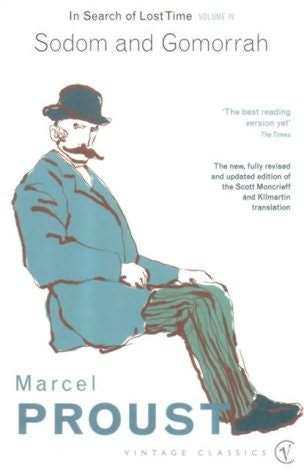

"In this fourth volume, Proust's novel takes up for the first time the theme of homosexual love and examines how destructive sexual jealousy can be for those who suffer it."

--The review--

In presenting us with yet more hundreds of pages of high society goings-on (or, perhaps more to the point, non-goings-on), Proust seems out to bore us. However, the situation becomes more interesting and poignant when St Loup and Swann reappear, and we agree more with Saint-Loup too, who seems to be suggesting that he is becoming bored with high society life, and by this stage in the epic French novel we readily acquiesce. These two characters are refreshing among the parade of faceless individuals and only slight movements of an amoebic conglomerate.

As with other volumes of In Search Of Lost Time, though, this fourth instalments is, by turns, eerily prophetic, sublime, and thoughtful. The narrator continues also to give us academic and philosophical food for thought: we are forced to consider our own narcissism, for one thing. Do we not all, in some way, consider our own lives as a cast of a few special ones moving against a background of superficial and two-dimensional others? If this is the case then Proust has replicated our own situations very accurately, even if this in a setting that contemporary readers do not recognise. On a more academic level, the discussion of the etymology of place names is relevant to the theme of name versus place raised in earlier volumes, but was interesting to me as a topic that I had considered as a subject of my master's degree thesis, so this interest may therefore not be so piqued for others. The same applies to the discussion of sex versus gender which takes place later in this volume. More universally intriguing is perhaps the nature of dream and sleep; Proust asserts his curiosity that we do not count the pleasures experienced in sleep as part of our everyday life's catalogue of happy moments.

The author is consistent in his inconsistency in the provision of gleams of light. The prose is still often impenetrable and opaque, and it is difficult to tell how much of this can be traced back to the author himself and how much of it can be laid at the translator's door. While certain gems keep the reader going, and such passages are clearly successful, these are counteracted by the lack of success found in the author's use of malapropism. The narrator's persona also continues to be difficult to deal with: while he is becoming more assertive, he is still manipulative, irritating, wimpish, neurotic and possessive, with his separation anxiety serving as an omnipresent undercurrent. This is simultaneously annoying and interesting as it does in some ways provide narrative momentum: we wonder, as a result of his nature, what purpose his relationship with Albertine really serves, and it is a relief to the readers to know that some of the servants featured in the novel also find his neuroses ridiculous, and that not everyone in the novel is taking the narrator as seriously as he is taking himself. The Balbec hotellier is another voice of reason - even though the narrator assumes that he says "I can tell you have nothing better to do" out of jealousy at not having been invited, the reality is that he says what the rest of us are thinking.

The reader longs for the narrator to return to the pleasant, peaceful and beautiful seaside retreat of Balbec in the hope of escaping the high society circles in which he has been moving in Paris. This unbearable circle of people is unfortunately not entirely left behind in the French capital, but this is slightly compensated for by other characters appearing who are more interesting - even if they are equally unconvincing, caricaturish, and an embodiment of petty inside politics. The audacity and tactlessness expressed by some of these members of the gentry would be hilarious with the right delivery, and further comedy can be ferreted out from the Verdurins' fickleness.

It is difficult to link the title to the book's content, as its theme does not supply a consistent thread - apart from a few throwaway tidbits we are not given much. This is something to be grateful for in other ways, though - if the alternative were a full-on diatribe of the ilk found in Part 1, Chapter 1, then most readers would likely pass. Proust as a precursor to the Austenesque humour that is so known and loved in British society today provides light to contrast the narrator's indecisiveness; he really seems to want to romanticise the fact of him being a womaniser, and seems more in love with the idea of being in love than ever. We end the volume feeling that his continuing liaison with Albertine is going to be a very bad car crash to say the least, and wondering how the author will pick up the pieces.

Other works by Marcel Proust

Pleasures and Days (1896)

Swann's Way (volume 1; 1913)

Within A Budding Grove (volume 2; 1919)

The Lemoine Affair (1919)

The Guermantes Way (volume 3; 1920/21)

The Captive/The Fugitive (volumes 5/6; 1923/25)

Time Regained (volume 7; 1927)

No comments:

Post a Comment